The momentum behind wind-assisted ship propulsion (WASP) is undeniable. Shipowners, charterers, and regulators are increasingly relying on wind to cut emissions and fuel costs. Yet one question dominates the debate: how much can these systems really deliver?

The answer is not trivial. Predicting the performance of WASP technologies is essential not only for investment decisions but also for regulatory compliance and long-term decarbonization strategies. A shipowner contemplating a multi-million euro retrofit, a financier underwriting the loan, and a regulator calculating a vessel’s Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) all need trustworthy numbers. The challenge lies in balancing the accuracy and ease of use of prediction methods and tools: simplified approaches are quick to use but tend to produce overly optimistic results; high-fidelity methods provide confidence but demand expertise and computational power.

This article explores the current state of performance prediction, highlighting the role of ITTC guidelines in creating a common language, the value of simplified methods for stakeholders who need transparency and speed, and Caponnetto Hueber’s high-fidelity approach, which provides the depth and accuracy required for robust investment and compliance decisions.

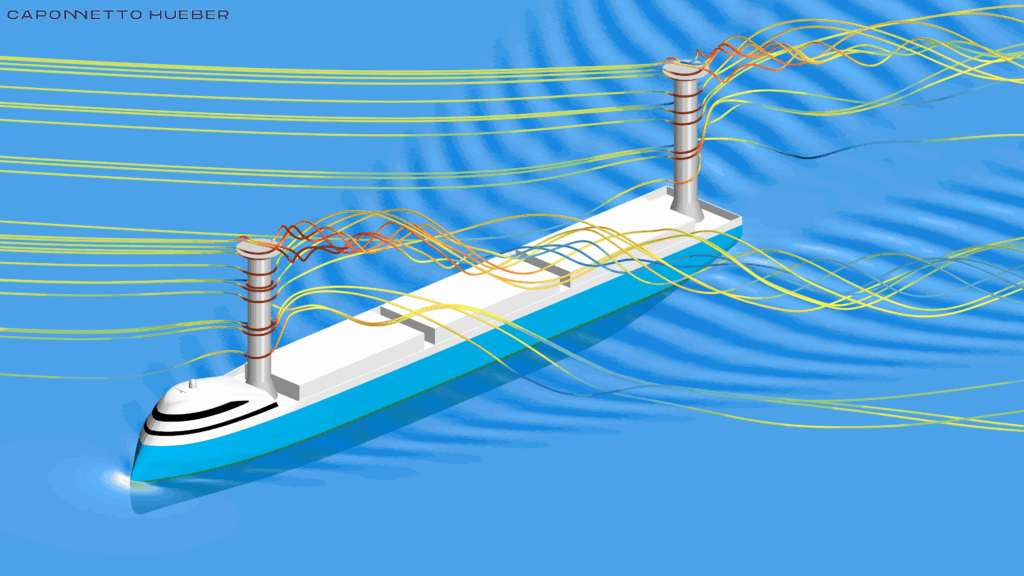

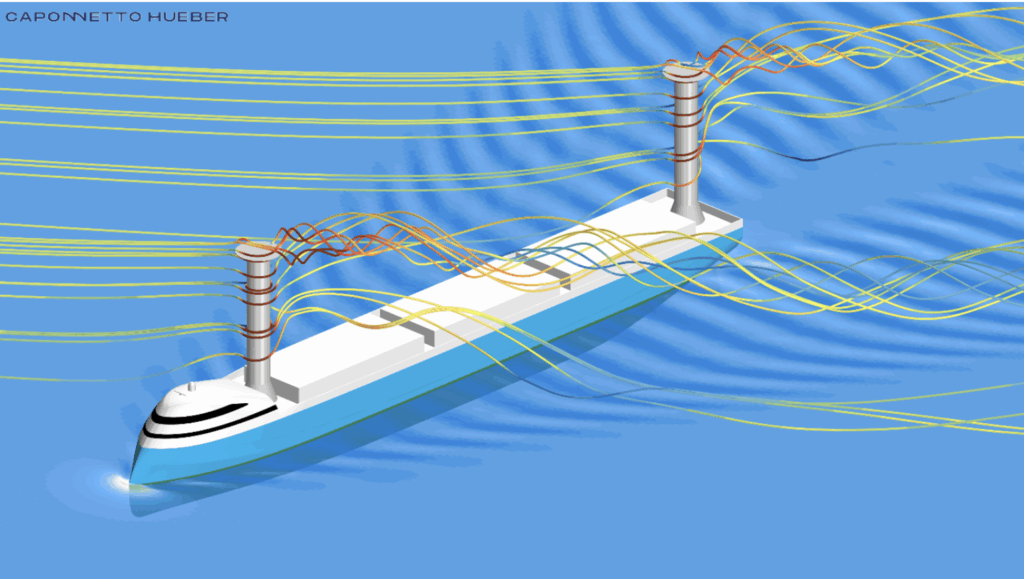

At the heart of wind propulsion lies aerodynamic efficiency. By generating forward thrust, WASP devices reduce the load on the main engine, thereby cutting fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions. However, the story does not end with the device itself. Performance depends on integration: the position of rotors, wings, or suction sails relative to the hull, superstructure, and with respect to each other can drastically change net efficiency. Capturing these interactions is one of the main challenges in performance prediction.

To understand how wind propulsion contributes to ship efficiency, the modelling approach is decisive. The industry relies on a wide range of methods: analytical formulas that provide quick but simplified estimates; semi-empirical models which blend measurements with assumptions; and numerical simulations to capture the complex aero-hydrodynamic behavior of ship and systems in detail. The choice between these approaches is not trivial. It directly influences the predicted thrust and, by extension, the projected efficiency gains of the vessel.

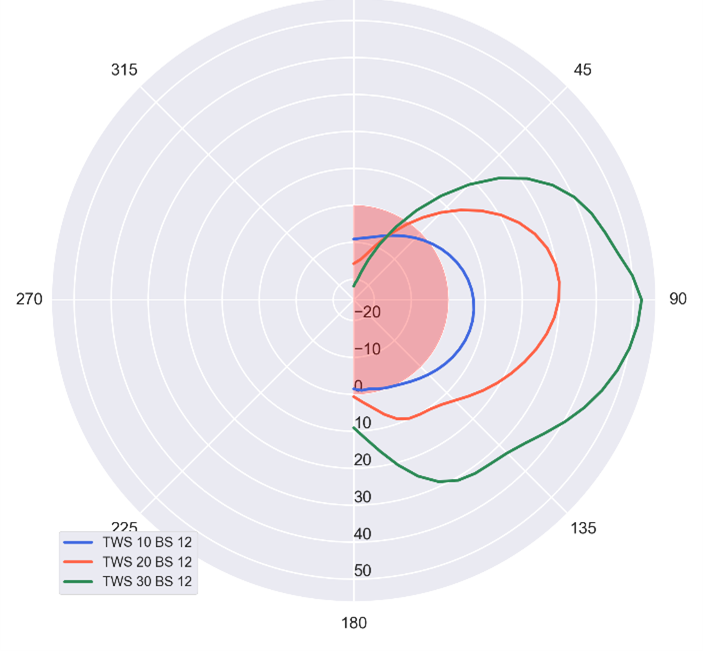

Performance prediction begins with the creation of polars, graphs mapping power or thrust versus sailing conditions (boat speed and true wind speed and angle). These polars are generally computed within a Velocity Prediction Program (VPP) that accepts arbitrary interpolation models as input. These models interpolate all the ship component’s forces and moments for any sailing and attitude condition in the optimization domain. The sailing conditions are parametrically swept so that the balance is optimized on each possible point of the power consumption polar. This polar represents the best predicted equilibrium solution, including the WASP devices’ trim controls that can be achieved at each sailing condition.

Routing is the final step in assessing WASP performance and is strongly dependent on the specific trade route and operating profile. Because of this, different technologies may excel under different conditions, meaning the best-performing system is not universal but closely tied to how and where the vessel is used.

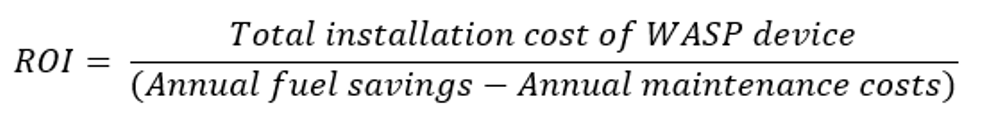

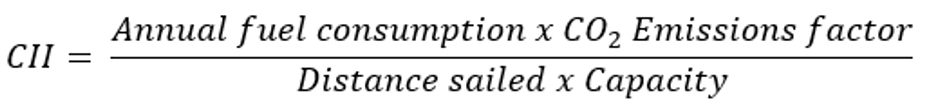

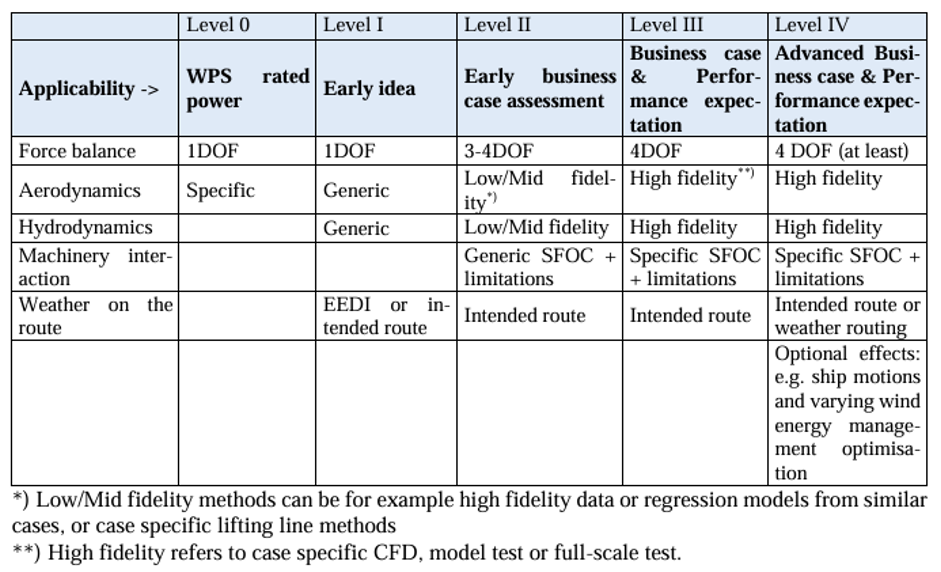

While measures such as net thrust or power savings are valuable for engineers, they vary greatly depending on the type of device, its configuration, and the chosen route, making them difficult to compare consistently, especially for non-technical stakeholders. At the decision-making level, what is needed is a common basis that allows different options to be compared in simple, financial, and regulatory terms. What truly matters today is how WASP technologies contribute to regulatory compliance and financial viability. For both shipowners and regulators, two KPIs stand out:

The result indicates the time in years it will take the fuel savings to fully cover the cost of the investment, giving shipowners a clear view of when the WASP device will start generating net savings. It is emphasized that any additional factors, such as CO2 emissions taxes, which can impact costs or savings, should be incorporated into the calculations.

The result is expressed in grams of CO₂ per nautical mile per ton of cargo (gCO₂/nm·ton). The formulation includes both the attained CII, which is calculated annually based on the vessel’s performance, and required CII, a benchmark that ships must meet, which becomes more stringent over time due to mandated reduction factors. These rating boundaries vary based on ship type, gross tonnage, and operational profiles

Together, these KPIs bridge the technical and commercial worlds: CII ensures a vessel can operate in a tightening regulatory environment, while ROI determines whether the investment makes financial sense. Both indicators are very sensitive to the performance estimation, so accurately predicting WASP performance therefore means delivering robust predictions that reflect real operational conditions.

For years, the absence of standardized procedures undermined confidence in WASP performance claims. Different providers used different models, leading to results that were often inconsistent and difficult to compare. This has created uncertainty for shipowners, regulators, and financiers trying to evaluate different options on a common basis.

This gap began to close with the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC), which in 2024 published its Recommended Procedures and Guidelines for Wind Powered and Wind Assisted Ships. For the first time, the industry has a structured proposed framework for assessing wind propulsion performance, with definitions, KPIs, and test methods agreed at an international level. However, there is still much work to be done. We have a long way to go to polish the proposed methods until the necessary level of accuracy and robustness is achieved.

A long-standing challenge in wind propulsion has been the absence of common KPIs. Savings from a wind propulsion technology (WPT) can be expressed in different forms, power, fuel, energy, or CO₂ reduction. Although these measures generally lead to the same ranking when comparing systems on the same vessel, the way they are presented strongly influences how different stakeholders perceive them. Shipowners and operators tend to think in tonnes of fuel saved per day, engineers prefer aerodynamic coefficients or power/energy-based metrics, while regulators and policymakers are primarily interested in CO₂ reductions. This fragmentation in language has made comparisons inconsistent and has slowed down confident decision-making and investment.

The ITTC addressed this issue in its 2024 Recommended Procedures. Section 5 consolidates concerns raised through focus group discussions held in 2022, where stakeholders from across the industry debated about how KPI should be:

The ITTC further emphasizes that KPIs should follow the vessel lifecycle, evolving from simple to more complex as designs progress. In practice, this means polars, routing, and savings must all be reported in a transparent, standardized way. Without harmonized KPIs, the sector risks confusion and delayed adoption; with them, wind propulsion can be evaluated credibly and fairly.

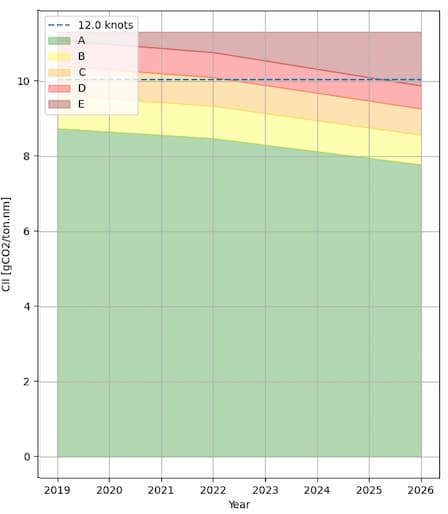

The ITTC guidelines establish five assessment levels, creating a progressive ladder of complexity and accuracy:

This methodology provides a common language for shipowners, regulators, and technology providers. It recognizes that different stakeholders require different levels of detail: an early feasibility study may only justify Level I methods, but a shipowner committing to a retrofit or a regulator calculating compliance must demand Level IV-grade confidence.

Not all stakeholders require the complexity of Level IV studies. Regulators, certifiers, and financiers benefit from transparent, simplified methods that allow for rapid assessments. The ITTC framework provides that accessibility by codifying Levels 0–II.

It is important to note, however, that simpler does not mean inaccurate. Even basic methods must be able to provide consistent trends if they are to enable fair comparisons between technologies. Achieving this is perhaps the greatest challenge. The industry would like the clarity and speed of a simple formula that reliably predicts outcomes, yet the physics involved are inherently complex. The aerodynamics of sails and rotors, their interaction with hull and superstructure, and the influence of weather and routing cannot be fully captured by shortcuts.

The market still lacks simple methods that can consistently reflect reality in this way. Advances in data analysis and machine learning may eventually close part of this gap, allowing trend-based estimations to be made from large datasets of operational results. But when it comes to calculating the actual magnitude of fuel savings or the optimal configuration for each device on board, advanced modelling will remain indispensable.

In short, lower-level methods are useful for early screening and engagement, but when millions of euros in retrofit investments are at stake, or when long-term compliance with CII trajectories must be demonstrated, high-fidelity approaches must serve as the benchmark.

As mentioned before, simplified or semi-empirical approaches are valuable for quick estimations, but they cannot capture the complex physics of ship-device-environment interactions. Critical phenomena such as wake effects, device-to-device shielding, or even the penalties at the propeller, whose design operating point shifts when WASP systems are installed, are often overlooked. This leads to optimistic projections that could undermine credibility when real-world performance falls short.

Caponnetto Hueber’s High-Fidelity (HF) methodology eliminates this gap by combining advanced computational fluid dynamics with smart technics for modelling. Although computationally demanding, full-scale CFD RANS simulations form the backbone of this approach, allowing us to capture the coupled aerodynamic and hydrodynamic behavior of vessels with their devices under realistic conditions. The methodology is detailed in our paper High-Fidelity Modelling and State-of-the-Art Evaluation of WASP Systems’ Fuel Savings on Major Shipping Routes, published in the RINA Wind Propulsion 2024 Proceedings.

The workflow begins with a case study definition: specifying ship type, routes, device number, and layout configurations. Using Design of Experiments (DoE) sampling and surrogate modelling techniques such as Kriging or Gaussian Process Regression, the design space can be mapped efficiently without requiring exhaustive CFD runs. The CFD campaigns themselves use RANS-based full-scale simulations that resolve the performance of each vessel component: hull, propeller, and superstructure with the WASP devices together, since standalone device models are insufficient and can produce misleading results.

These simulations feed into a Performance Prediction Program (PPP), which generates vessel-specific polars and predicts power demand under different sailing conditions, including optimized trim. These polars are then embedded into a weather routing solver that uses ERA5 reanalysis data and graph-based Dijkstra algorithms to optimize routes for minimum fuel consumption, while accounting for wind and waves. Finally, the outputs are translated into decision-grade KPIs such as CII and ROI, making the results directly relevant for regulatory compliance and investment decisions. This pipeline delivers investment-grade predictions, enabling owners to take decisions backed by scientific rigor.

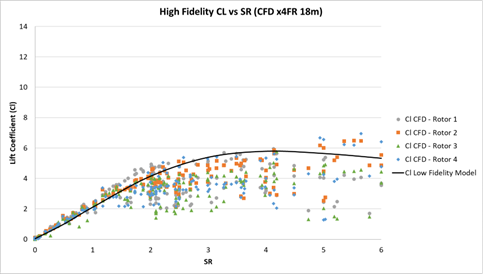

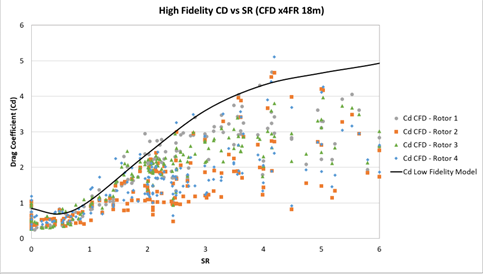

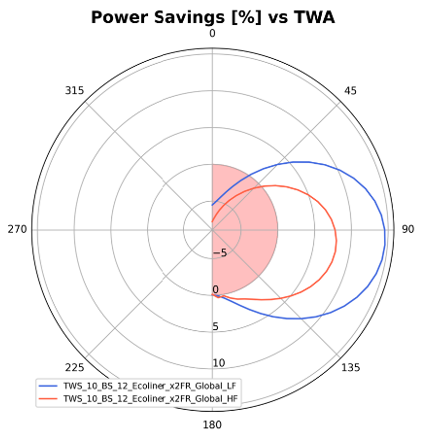

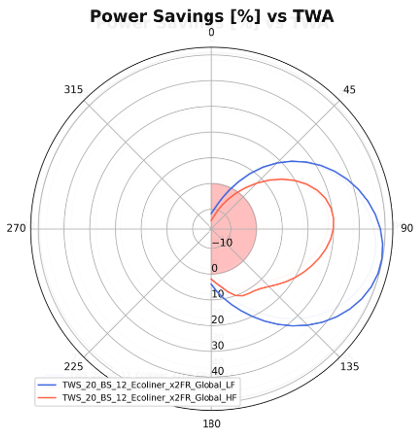

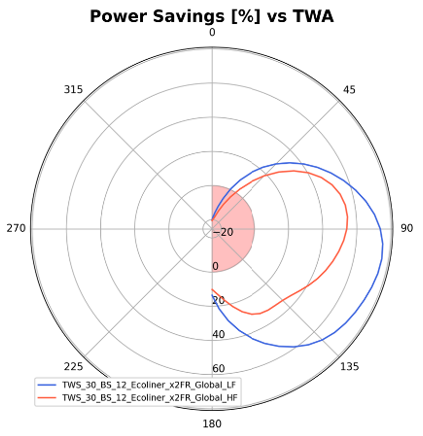

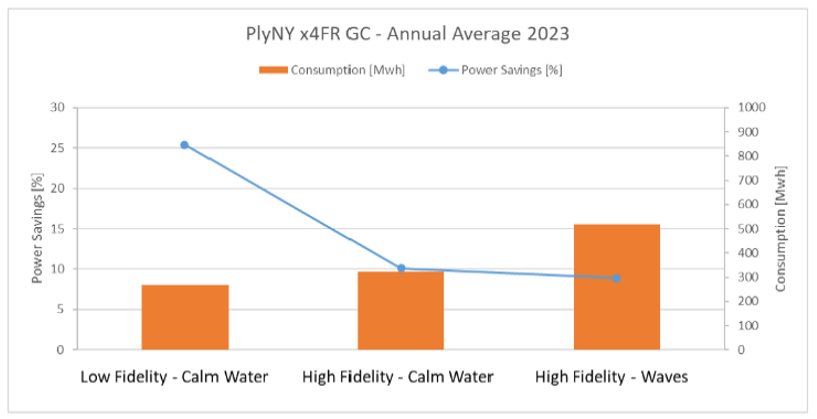

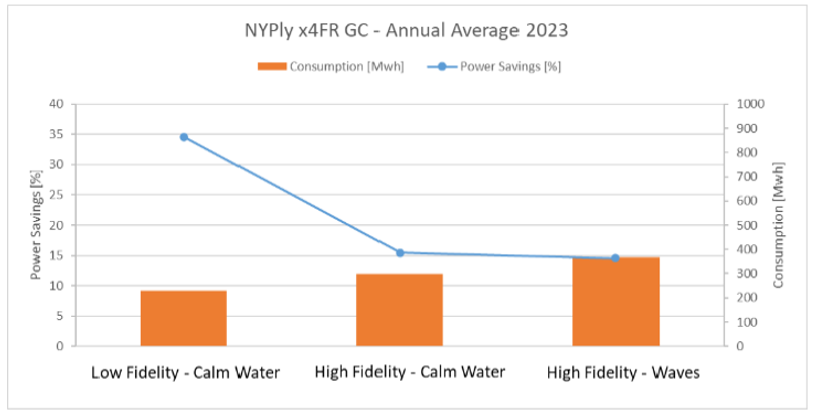

The value of this approach becomes clear when comparing low-fidelity (LF) and high-fidelity (HF) modelling for WASP aero performance. In our Ecoliner case study, fitted with two and four Flettner Rotors, the LF models were based on literature lift and drag coefficients, isolated rotor performance (plus hull and superstructure aero drag). Device-device and hull-device interaction effects were not considered to highlight the differences when these effects are not included in lower fidelity approaches.

The results at polar level showed over optimistic power savings results for LF modelling at all sailing conditions. By contrast, HF simulations showed that increasing the number of rotors does not linearly increase savings; interaction effects between devices and shielding losses significantly reduce efficiency. The differences between LF and HF have also a great impact in terms of ship optimal balance, including the optimal operating range of the propeller and the aerodynamic devices.

Additionally, incorporating route optimization allows WASP devices to reach their full potential by exploiting favorable wind conditions and minimizing sea state penalties. The impact on both CII ratings and ROI is significant: the case studies showed that when waves and optimized routing are included, the difference in payback compared to calm-water LF assumptions over the great circle is dramatic, shifting from a marginal business case to a clearly attractive investment.

These findings highlight a fundamental truth: errors compound along the modelling chain. Inaccuracies at the aerodynamic level propagate downstream into power prediction, weather routing, ROI, and ultimately CII compliance. As fidelity increases, predicted savings consistently converge toward lower, but more realistic values.

Accurately predicting WASP performance is more than an academic exercise, it is the foundation of trust in wind propulsion. The ITTC has created a vital framework for comparability, while high-fidelity modelling provides the depth needed for investment-grade decisions.

Caponnetto Hueber’s HF methodology provides that reliability. By combining advanced CFD with surrogate modelling, performance prediction programs, and realistic routing simulations, it ensures that wind propulsion systems are evaluated with the rigor they deserve. For shipowners, this means investment decisions are backed by science rather than optimism; for regulators, it provides credible numbers for compliance; and for the industry as a whole, it sets a new standard for how wind propulsion performance should be measured.

At this stage in shipping’s decarbonization, WASP systems cannot afford to be judged on exaggerated claims or optimistic shortcuts. Only by embracing rigorous, transparent, and standardized performance prediction can the industry unlock the full potential of wind propulsion, transforming it from a promising innovation into a mainstream solution on the path to IMO’s 2050 net-zero goal.

References

During the 33rd America’s Cup cycle, Mario Caponnetto contributed to hydrodynamic assessment workstreams aligned with the BMW Oracle wing-sail platform, the configuration that ultimately won the Match. This milestone marked the shift toward aero-hydrodynamic integration in Cup design culture.

BMW Oracle Racing

America’s Cup / Aero-Hydro Integration / Performance Engineering

In 2021, Caponnetto Hueber led the CFD, foil design, and hydrodynamic engineering for the AC75 of Luna Rossa Challenge, the eventual Prada Cup winner. We deployed multiscale CFD and aero-hydro coupling to ensure optimum lift and control. Rapid iteration delivered performance gains under tight competition timelines.

Luna Rossa Challenge

Racing Concept / CFD / Foil Design